Kingston Today, Move-In Weekend 2025

It’s Labour Day weekend, 2025, and Kingston is transforming once again. U-Hauls and rental vans line the narrow streets of the student ghetto. From my front window, I can see families wrestling bulky furniture and boxes out of the back of vans — hauling them up steep staircases into the old Victorian houses that have long since become student rentals, or squeezing it all into the elevators of the new condo towers that now dominate Princess Street. Once the parents leave, the same cycle begins — trips to Canadian Tire, Wal-Mart, and the grocery stores, just like it always has.

Frosh Week — that’s what we all called it in 1976. Officially, it may have been “Orientation Week,” but I’ve never met anyone who used that term. This far removed, I’m not even sure what it’s called now, but I hope the name has survived.

Queen’s Traditions Before 1976

I tried to pin down when Frosh Week, in the modern sense, actually began — and it seems the week-long version didn’t really take shape until the early 1950s. Before that, Queen’s still had “initiations,” though they were a lot rougher, according to the Queen’s Journal

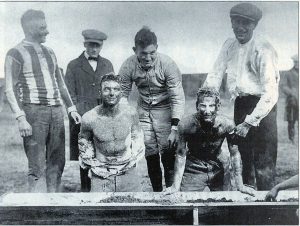

In the early 1900s, they held “rushes” — essentially free-for-all brawls between freshmen and upper-level students. First-years were smeared with molasses and feathers and shoved across campus for everyone’s amusement.

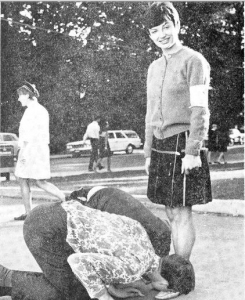

By the 1920s, things were more organized, though no kinder. Hazing was written right into the AMS constitution. Male frosh had to carry umbrellas everywhere and keep matchboxes handy to light cigarettes for upper-years. Dating was banned until after Christmas exams — imagine paying tuition only to be told you couldn’t go on a date until January.

From day one, “traditions” like dead horses,

duck walks, and endless pushups, often with a frosh of the opposite sex underneath you, were the official welcome to Queen’s.

None of it sounds particularly welcoming now, but in those days, it was sold as Queen’s spirit.

By the time I arrived in 1976, some of the harsher customs had faded. However, the spirit of Frosh Week — somewhere between serious and ridiculous — was still alive. That year would turn out to be historic: the first time women joined the Engineers in their legendary grease pole climb. Officially, women weren’t allowed — “health and safety reasons” was the excuse — but sometimes rules are made to be broken.

My First Frosh Week

When I arrived in Kingston in September 1976, I was a Toronto kid who spent plenty of time on the Yonge Street strip, ducking into record stores several times a week. Maybe that made me a bit snobbish about “small-town Kingston.” At the time, it felt like I was giving something up to be here. That attitude would eventually lead to a drive back to Toronto after the first week of classes — but more on that later.

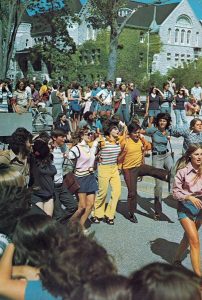

My first taste of Queen’s came that opening night at Leonard Field, when hundreds of us were corralled together to learn the Oil Thigh. Nervous frosh shouting words we barely understood, arms locked, voices bouncing off the limestone — it was chaotic, loud, and impossible not to get swept up in.

Later that same night, two acquaintances I knew from Toronto and I wandered over to the campus pub, then called The Underground. The doorkeepers hesitated about letting us in without student cards, but we had our Frosh pins on. I’d already stuffed my tam in my pocket. That was enough, and once inside, we found cheap, plentiful beer and a room full of upper-years who already had it all figured out.

The next morning, we were divided into Gael groups, each led by a couple of second-year students. I landed in Group 86. One of the guys in my group was Danny Murray — as far as I remember, the only local not living in residence. Danny knew Kingston, and I came to appreciate that a couple of times that week.

That week also included the downtown tour and a trip over to Wolfe Island for a cookout. I drove my car straight onto the ferry, not realizing there was a line-up system. Danny just smiled and said the crew were used to Queen’s students cutting in. Nobody seemed to mind. We stayed in the car for the twenty-minute ride — safer not to give anyone the chance to say anything.

On the island, Danny led us to a stretch of flat rock along the shoreline where we lit a fire and roasted hot dogs. No beer for once, just pop. I doubt you could do that now — especially after this year’s drought, and with so many houses built along the shoreline over the past fifty years. Back then, it was mostly farmland, so all we disturbed were cows and assorted wildlife.

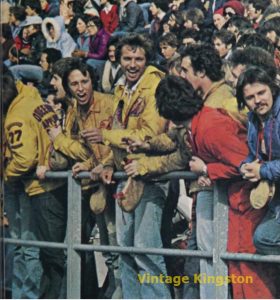

Saturday at Richardson Stadium

One of the big highlights of that first week was the football game. Hundreds — if not thousands — of frosh and upper-years marched along Union Street toward Richardson Stadium on West Campus. No traffic could get through, and the people in those beautiful old houses along Union were taking it in through their windows whether they wanted to or not. Even if they weren’t watching, they could certainly hear the chants — the Oil Thigh and the booming call-and-response of “What’s the Sport of Kings?” “Queen’s! Queen’s! Queen’s!”

Before the 1970s, Richardson Stadium had been located on the main campus, but by 1976, it had already been relocated. And like the old Kingston traffic circle, it was one of those things people talked about that was gone before my time.

Before the 1970s, the stadium had been located on the main campus, but by 1976, it had already been relocated. And like the old Kingston traffic circle, it was one of those things people talked about that was gone before my time.

The game itself was unlike anything I’d experienced before. This wasn’t polished, professional sports. Students carried wineskins into the stands, and the whole thing felt more like a giant party than an athletic contest. The crowd was rowdy, loud, and fully engaged with the show.

Not far from the stadium stood the old Kingston Penitentiary water tower. We knew it was just a water supply, but the urban legend at the time claimed it had been used for hangings. It added a bit of dark colour to the landscape, the kind of story that stuck in your head as a frosh even if it wasn’t true.

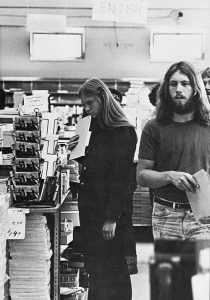

By the end of that first week, reality also crept in. We Arts students had to make our class choices and, like everyone else, make the expensive pilgrimage to the campus bookstore. Armfuls of weighty textbooks came with a bill that rivaled a month’s rent, and walking out of there was the moment university life felt very real

Mud, Tomatoes, and the Grease Pole

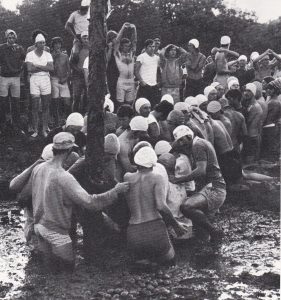

The crown event of Frosh Week was the trek out to Highway 15 to watch the Engineers tackle the grease pole. The buses carried us to what seemed way out into the country; across the causeway, through Barriefield, and up Highway 15 to a piece of land Queen’s owned. Back then, it was almost entirely farmland. Today, that same plot is now home to the Riverview Shopping Centre and a Food Basics store.

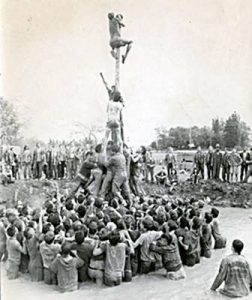

The setup was straightforward but brutal. In the middle sat a pit filled with water, animal intestines, and other foul liquids. A 30-foot pole rose from the centre, greased top to bottom, with a tam nailed to the top. The first-year engineers arrived in U-Haul trucks, and after only a few moments to reflect, they were herded straight into the pit.

The truck roofs quickly filled with upper-year engineers and their baskets of rotten tomatoes — and anything else they could throw — to make the tam that much harder to reach. Down below, the frosh wore bathing caps to at least keep the foul water and flying tomatoes out of their ears.

The strategy was to build a human pyramid, climb, and grab the tam. The reality was collapse after collapse into the muck. That year, the upper-years had nailed the tam in with spikes. At one point, a woman frosh ended up hanging from the tam itself as the pyramid gave way beneath her. 1976 marked the first year women were included in the climb. Officially, they weren’t allowed — “health and safety reasons” was the excuse — but rules were made to be broken. When the tam finally came down, she was second from the top.

In later years, things would be scaled back. By 1984, the grease pole had become too much — too many projectiles, too much filth, too many students headed to the hospital — and the university finally began imposing limits. But in 1976, Queen’s was still in its unpolished era of traditions, and I saw it firsthand

Purple Jesus and Lake Ontario Park

If there was one constant running through Frosh Week in 1976, it was the drinking. Every night, you could walk through the student ghetto and find house parties. They weren’t like the infamous Homecoming blowouts of the last decade or so, but there was no shortage of beer — and no shortage of Purple Jesus.

Purple Jesus wasn’t anything fancy. It was high-proof vodka or “Alcool” mixed with grape juice or purple Kool-Aid, and sometimes whatever else was handy. Sweet enough to cover the taste, strong enough to knock you sideways — and it showed up everywhere.

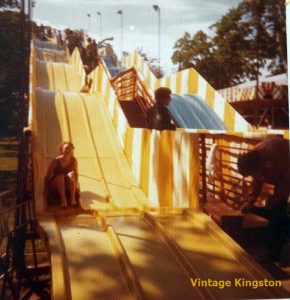

One of the more organized outings that week was a trip to Lake Ontario Park. Back then, it still had rides, games, and mini-golf, and the place had the feel of a small-town carnival. There was also a popular beer tent, which drew just as many students as the rides. It wasn’t sophisticated, but it fit Frosh Week in those days perfectly.

Life in Residence (1976)

Living in residence was a whole new world for me. Co-ed floors, double rooms, and the constant buzz of activity. But what really stands out are the meals. Three times a day, we trooped into Leonard Cafeteria, served by Saga Foods. The quality was… let’s say “variable.” Upper-year floor seniors swore it was still an improvement over the year before, when Beaver Foods ran the place.

The cafeteria had its own traditions, none of them official. One I remember clearly was the jello trick. If you gave it the right spin on the way up, a cube of jello could hit the ceiling and stick there for weeks — sometimes even months. It was probably the most reliable thing on the menu.

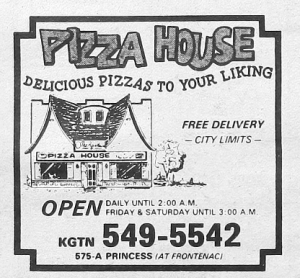

And of course, we all quickly learned the phone numbers of the local pizzerias. The favourite at the time was a place called Pizza House, which is now long gone; the site is now covered by one of the condo towers. Back then, though, it was the go-to option for late-night orders when cafeteria food didn’t suffice.

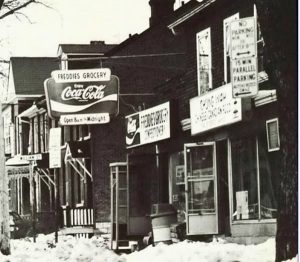

Residence also came with its own social life. Each floor had a “common room”, and as the year went on, those spaces got busier. Stereo wars were standard, one person blasting Dark Side of the Moon while someone else cranked Zeppelin to drown it out. Sundays had their own twist too: the cafeterias only served breakfast, so you were on your own the rest of the day. The standard room fridge and stove got a workout, and some people never advanced beyond Kraft Dinner… with gourmet “additives” like a can of tuna; often procured at Freddies, the closest store with a limited selection of groceries to campus. Besides it was Chung Wha Chinese Food, very popular on Sundays when there was no lunch or dinner for students in residence, and a wquick walk to the corner of University & William

A Drive Back to Toronto

After a couple of weeks in Kingston, homesickness hit. One weekend, two friends from North Toronto and I piled into my ’71 Valiant and headed back down the 401. The idea was simple enough: see some familiar places and remember why Toronto was still “home.”

I had it mapped out in my head — Saturday night at the Gasworks, one of the best spots for live music. During the day, I wandered downtown, stopping in at Sam’s and A&A’s to flip through records, something I’d done hundreds of times before.

But it wasn’t the same. Most of my friends were scattered off at their own universities — Trent, Western, Waterloo — or, in one case, working a year on a Great Lakes tanker. So instead of the Gasworks, I found myself at home on a quiet Saturday night. The city was still there, but the rhythm had changed.

It dawned on me that while Toronto was still exciting during the day, what I really wanted that Saturday night was to be back at Queen’s. Kingston was already starting to pull me in.

Finding Home in Kingston

Slowly, something shifted. At first, Kingston felt temporary — a place I’d be for a few years before heading “back home.” For the first two summers after classes ended, I did precisely that — packed up and returned to Toronto for summer jobs. But soon enough, I started staying here to work instead, and that was different. It pulled me outside the Queen’s bubble and into Kingston itself.

I found a lifestyle that wasn’t just residence life, lectures, and campus events. It was Kingston coffee shops, summer jobs, the lake, and neighbourhoods that had nothing to do with Queen’s. By the third year, I wasn’t just a student living in Kingston. I was a Kingston person who happened to attend Queen’s.

Later, after my four years at Queen’s, I knew: Toronto was where I came from, but Kingston was where I belonged. And I know I’m not the only one. Over the years, I’ve met dozens of people with the same story — they arrived here for Queen’s, thinking it was temporary, and either never left or found their way back later. There are likely thousands of us in Kingston who first rolled into town as frosh and ended up building a life here.

Watching Frosh Week from Downtown

I had always preferred working for myself, so a year after I left Queen’s, I opened my own store. At first, it was a record shop called Vinyl Vendor. However, as vinyl began to give way to CDs, the name started to feel dated, so I transitioned into a full-range gift shop that I called The Jungle.

And yes, we’ve already mentioned the flags — Canadian, provincial, Queen’s colours, rainbow, pirate — but I sold plenty more of them over the years. Alongside the flags came posters, clothing, wall hangings, décor, and even body jewellery. In many ways, the shop catered directly to Queen’s students, who came in seeking ways to make their rented rooms feel like home.

Running those stores kept me connected to the student body long after I graduated, and it gave me a front-row seat on how Frosh Week — and student life in general — was evolving. Every September, the cycle repeated. Parents dropping off their kids, U-Hauls clogging the streets, and soon after, new students wandering into my store. Some came for flags and posters, some for lamps, and some just to look. From behind the counter, I could see how the traditions were shifting year by year.

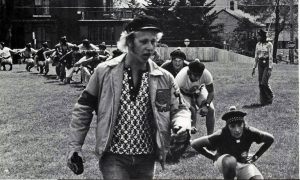

Now, of course, vinyl has made quite a comeback — and I still dabble a bit in online sales. Full circle, in its own way.[Insert: Shinerama, 1973]

Traditions Get Tested

By the 1980s and 1990s, Frosh Week was undergoing changes. Drinking was being de-emphasized, safety was becoming a bigger concern, and the rougher edges of the traditions were finally being questioned. The breaking point came in 1984, when FRECs threw urine, vomit, animal guts, cow heads, and rotten vegetables into the grease pole pit. At least 25 students ended up in the hospital, and the Engineering Society had to tip the pole over themselves, recording a “time” of 162 minutes. After that, restrictions started to pile on — projectiles were banned in 1985, axle grease was replaced with lanolin a few years later, and eventually the whole thing shifted into more of a team-building exercise than a hazing ritual.

The changes weren’t just in the events. The students themselves were changing too. When I first arrived in 1976, painter pants were in. By the 80s, those had been replaced by overalls, which quickly became covered in slogans, sayings, and inside jokes. The Engineering frosh leaned into the purple dye and mohawks. At the same time, everyone else was experimenting with new ways of making Frosh Week their own.

From my spot downtown, I could see both sides of it. Every September, the streets filled with chants and colour, but the tone was shifting. The “anything goes” attitude of the 1970s was giving way to something more regulated — safer, perhaps, but still carrying remnants of the old spirit.

Back to Today

Nearly fifty years later, Frosh Week still rolls on, even if it looks very different from the one I first experienced in 1976. The old initiation rituals aren’t emphasized in the same way anymore, drinking has been pushed to the background, and alcohol references have even been stripped out of Gael group chants. Along the way, there were missteps — offensive slogans, ugly signs, incidents that forced everyone to take a hard look. Frosh Week had to change, and lessons were learned.

One of the most significant shifts occurred with the elimination of Grade 13 in the province of Ontario. First-year students arrived a year younger than they did when I started, which changed the tone of orientation week in both big and small ways.

But the heart of it remains. Every September, a wave of new students arrives, and within days, they’re fully integrated into Kingston. I’ve seen it from every angle — as a frosh, a student, a grad, a store owner, and now as a long-time resident and Realtor. The faces change, the traditions shift, but the cycle is the same. Students move in, discover Kingston, and some of them never really leave.

For all the complaints about traffic, noise, litter, and purple-stained crowds, the truth is Kingston wouldn’t be the city it is without Queen’s. The students bring energy, ideas, and renewal, year after year. And as I watch the new arrivals today, it doesn’t seem that long ago I was one of them, stepping into Kingston for the first time.